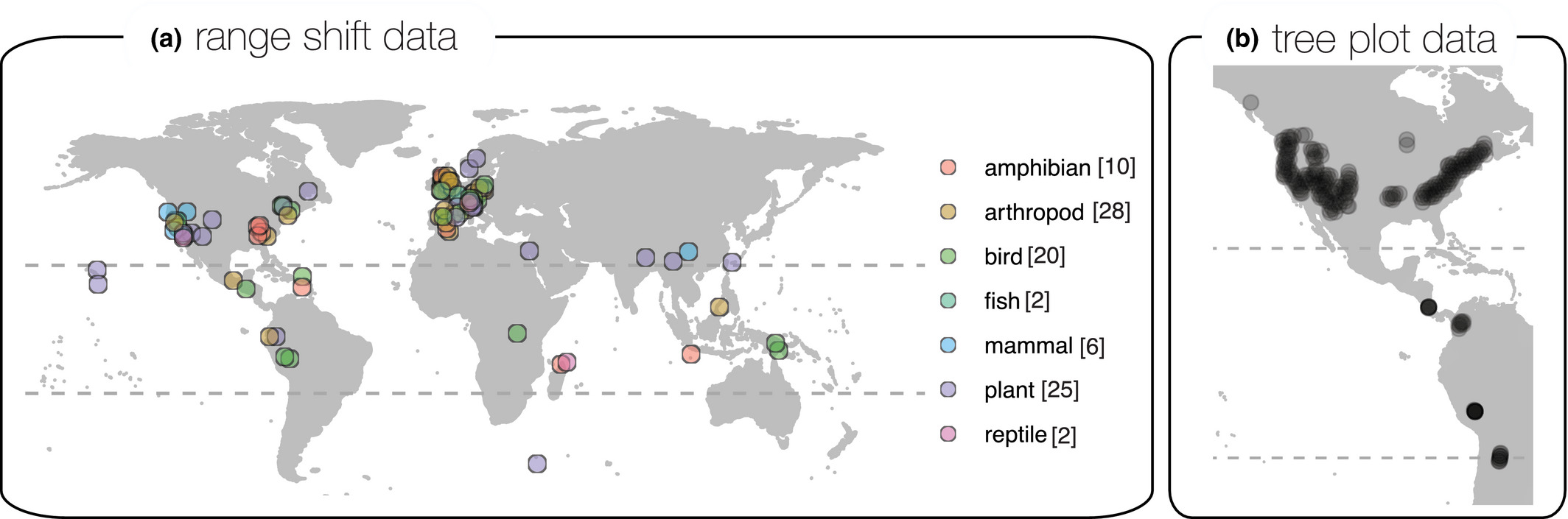

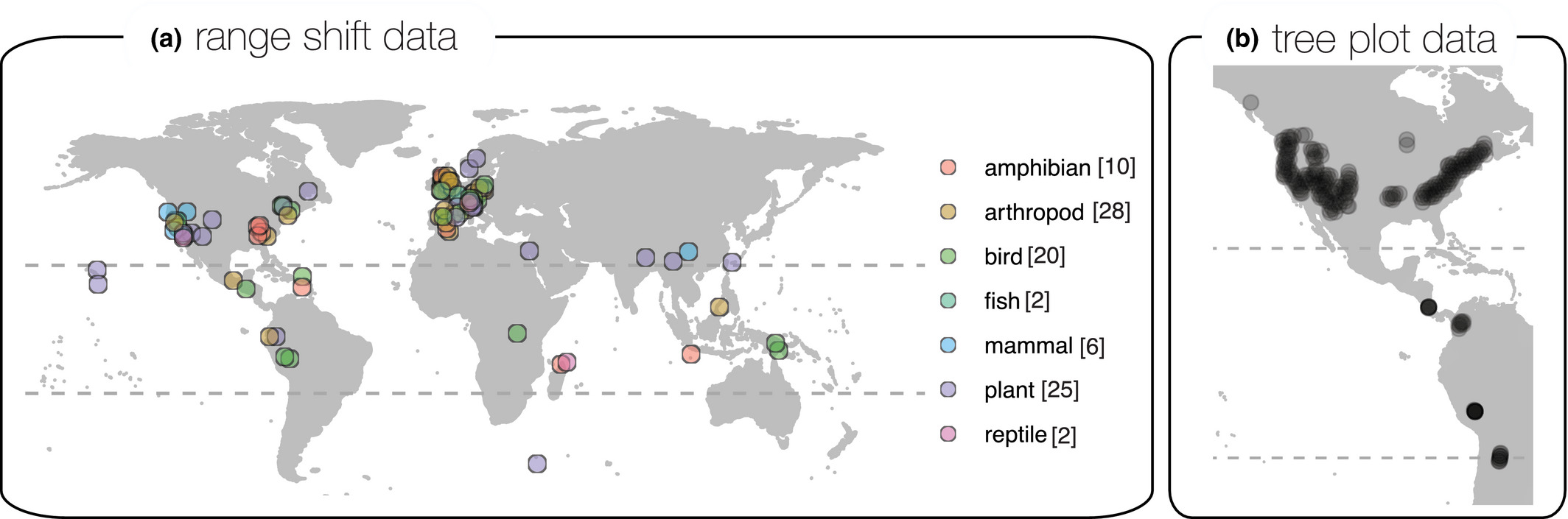

Range shift and tree plot datasets

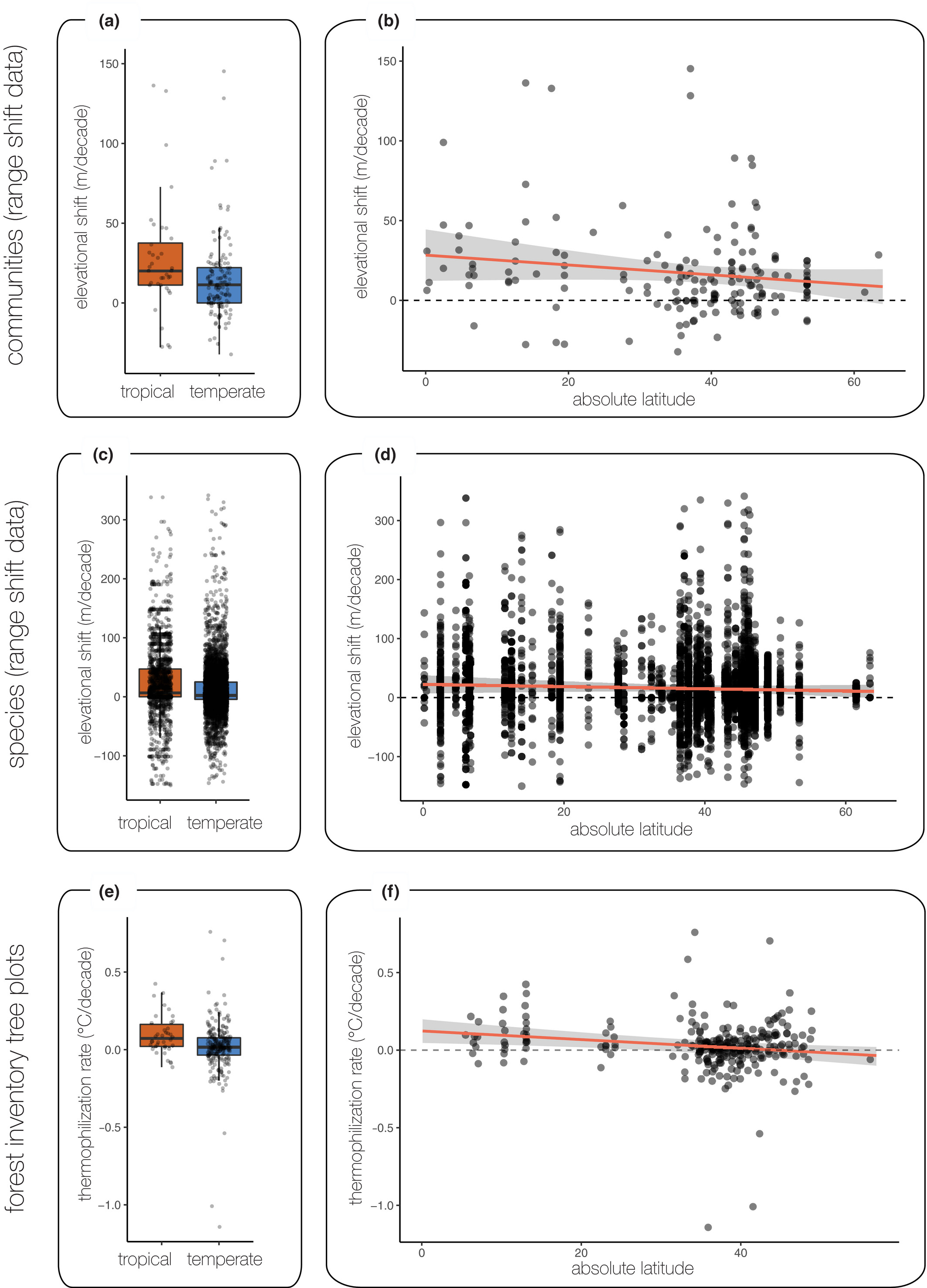

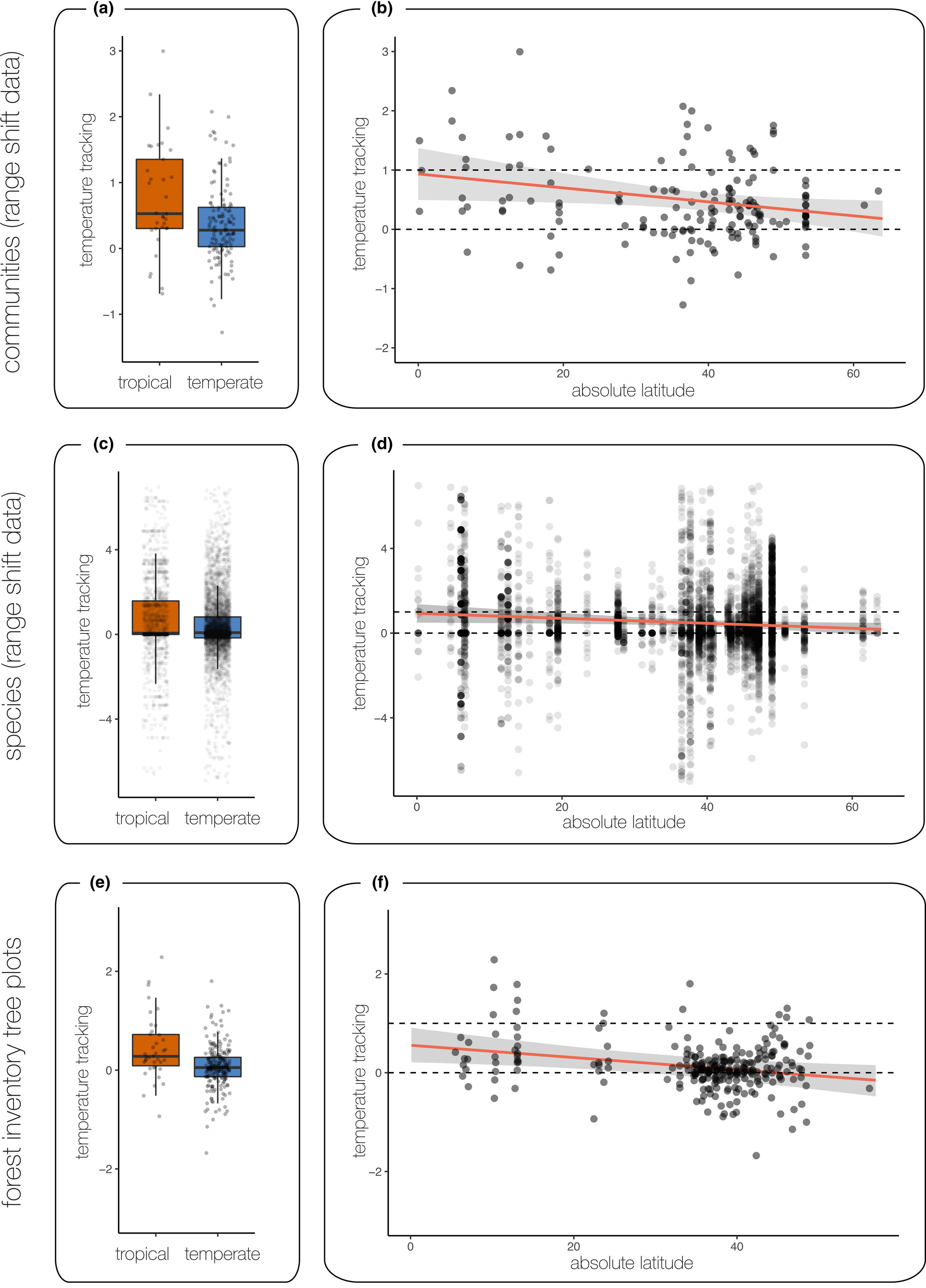

Many species are responding to global warming by shifting their distributions upslope to higher elevations, but the observed rates of shifts vary considerably among studies. Here, we test the hypothesis that this variation is in part explained by latitude, with tropical species being particularly responsive to warming temperatures. We analyze two independent empirical datasets—shifts in species’ elevational ranges, and changes in composition of forest inventory tree plots. Tropical species are tracking rising temperatures 2.1–2.4 times (range shift dataset) and 10 times (tree plot dataset) better than their temperate counterparts. Models predict that for a 100 m upslope shift in temperature isotherm, species at the equator have shifted their elevational ranges 93–96 m upslope, while species at 45° latitude have shifted only 37–42 m upslope. For tree plots, models predict that a 1°C increase in temperature leads to an increase in community temperature index (CTI), a metric of the average temperature optima of tree species within a plot, of 0.56°C at the equator but no change in CTI at 45° latitude (–0.033°C). This latitudinal gradient in temperature tracking suggests that tropical montane communities may be on an “escalator to extinction” as global temperatures continue to rise.