Climate and phenology veloity

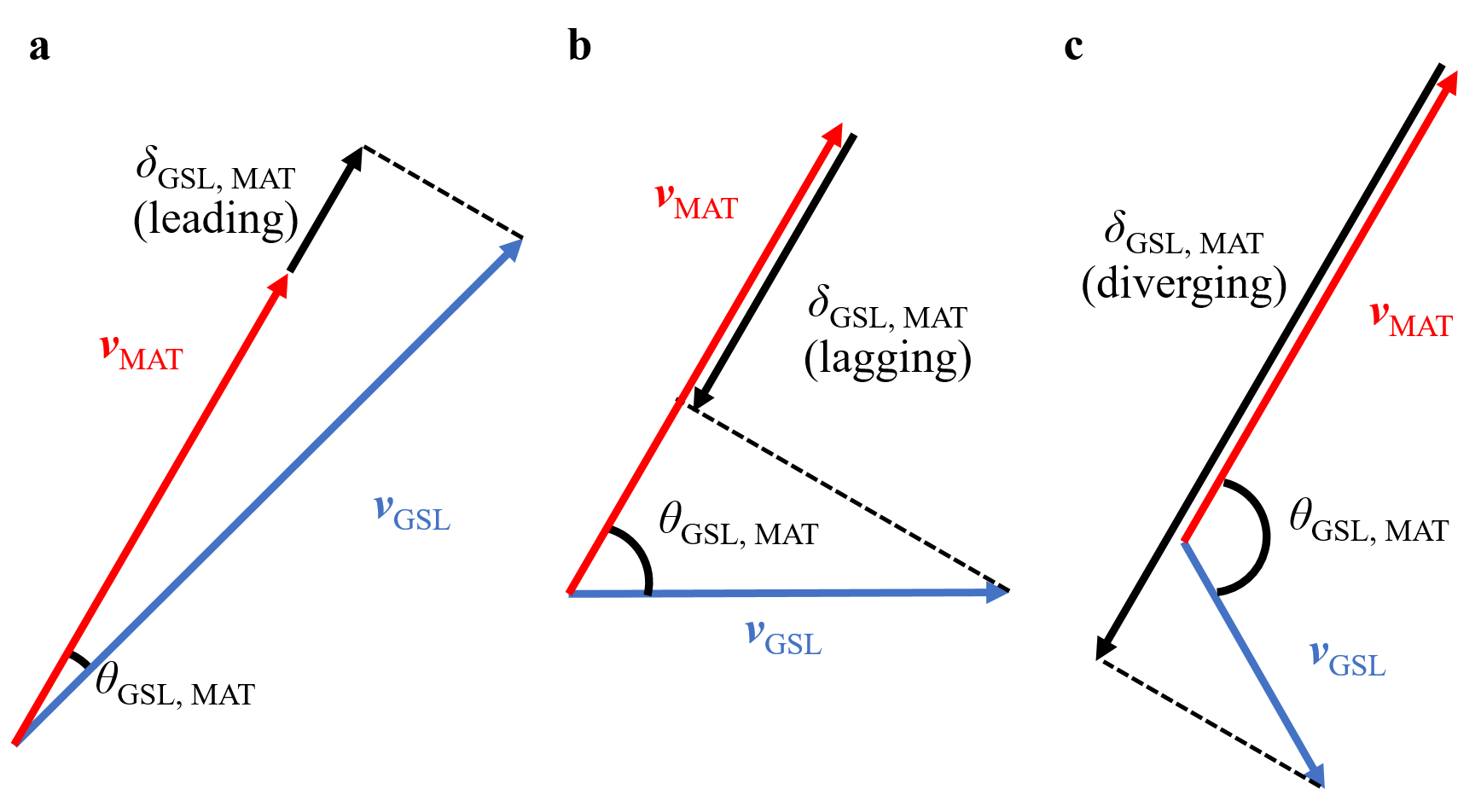

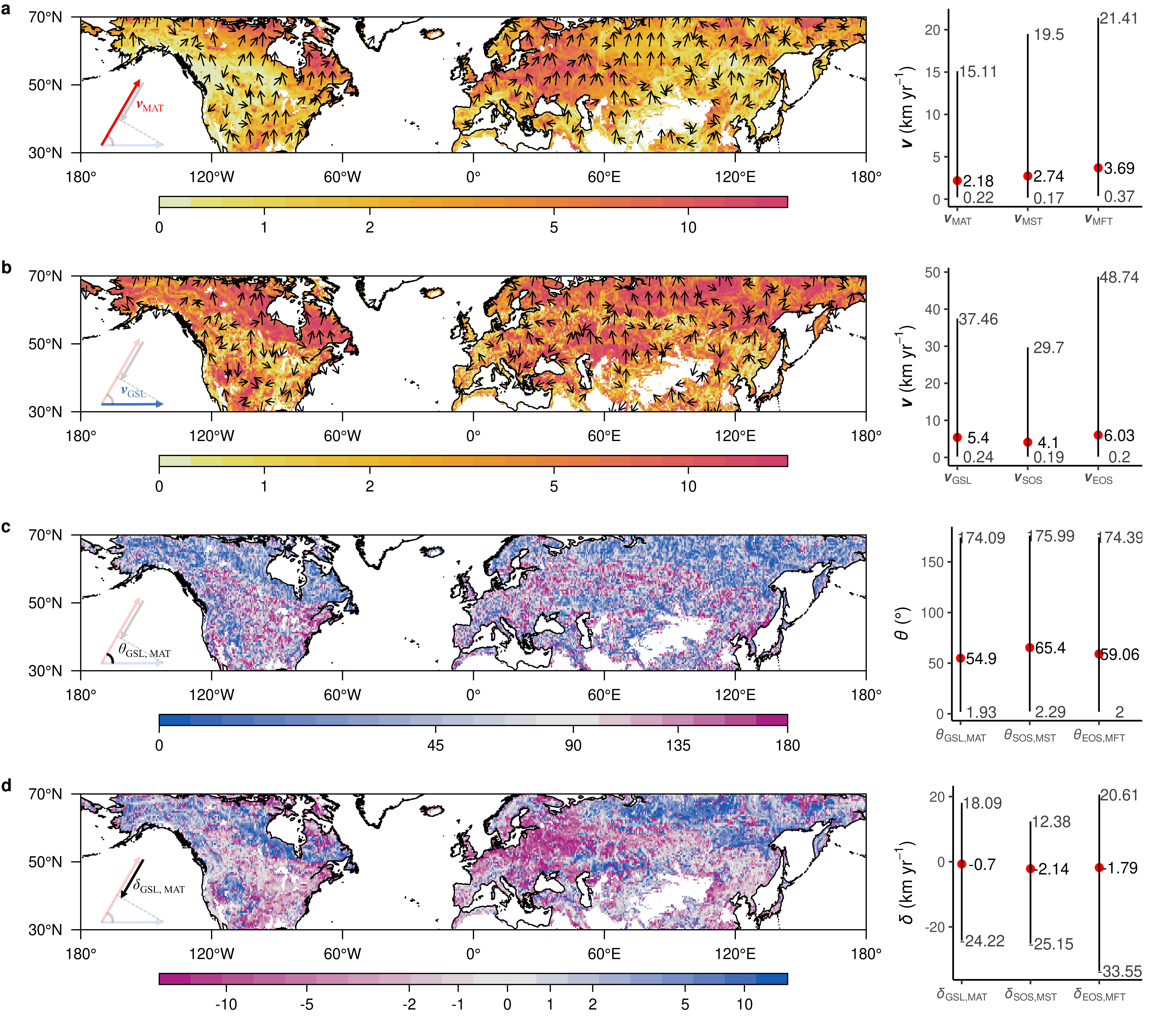

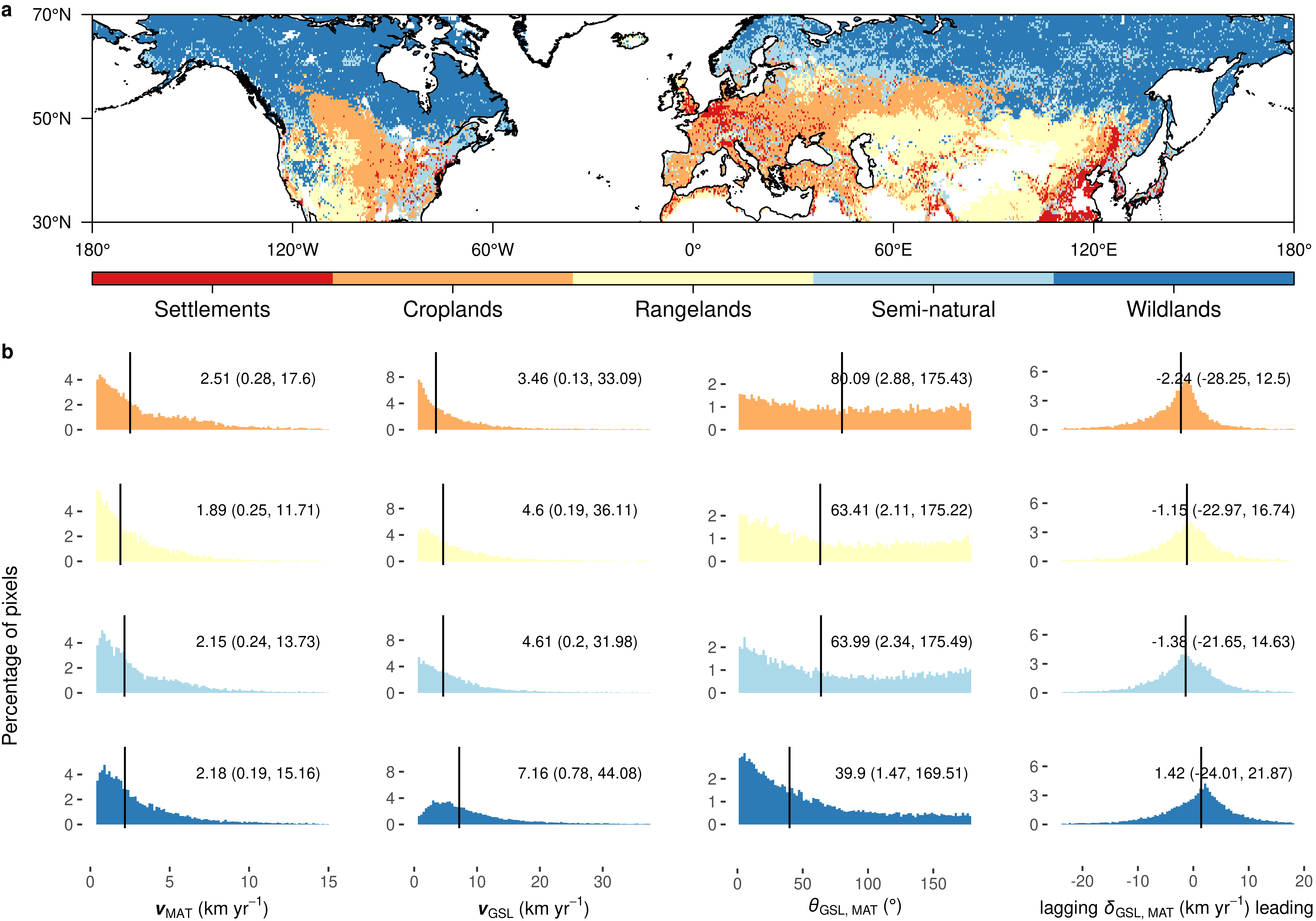

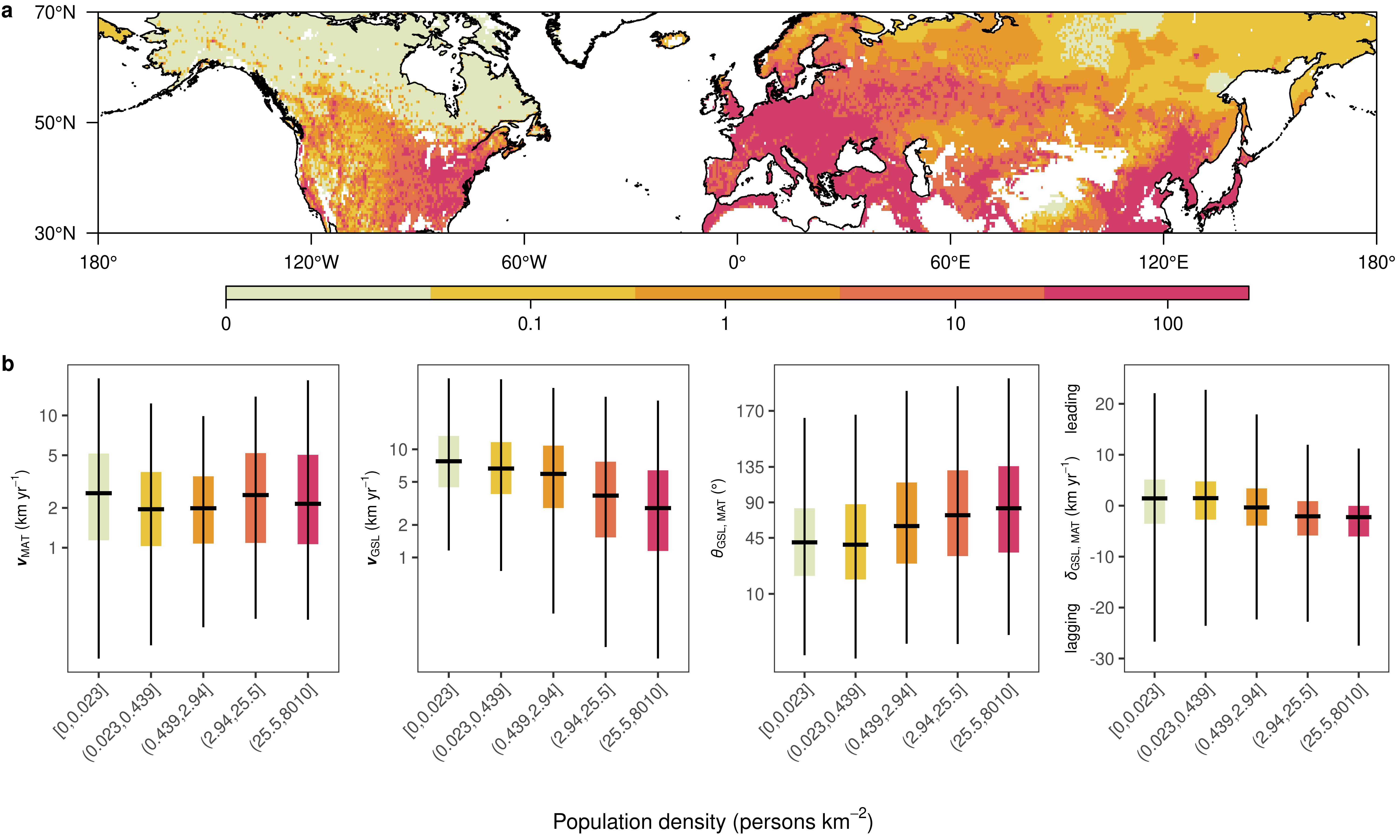

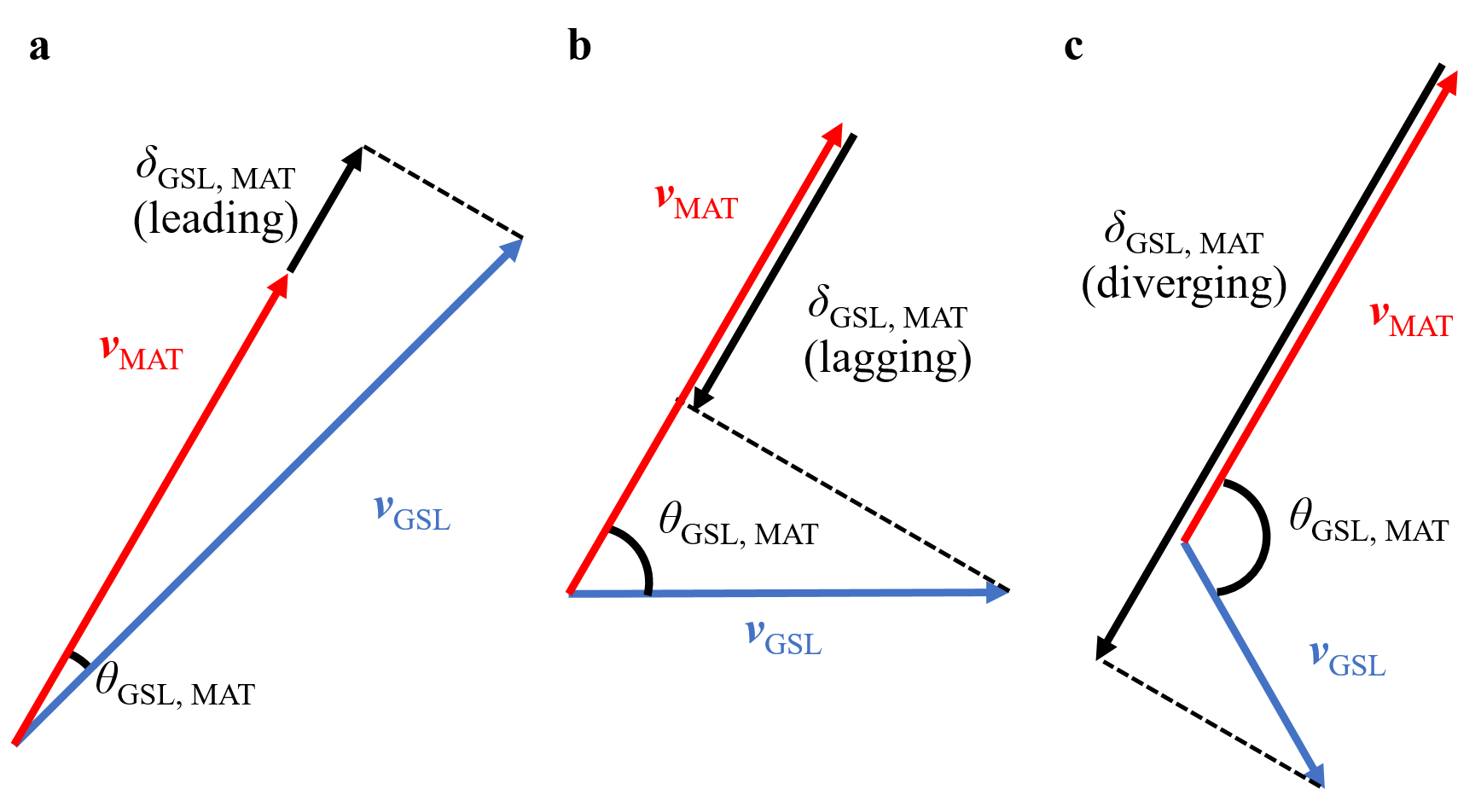

Plants track changing climate partly by shifting their phenology, the timing of recurring biological events. It is unknown whether these observed phenological shifts are sufficient to keep pace with rapid climate changes. Phenological mismatch, or the desynchronization between the timing of critical phenological events, has long been hypothesized but rarely quantified on a large scale. It is even less clear how human activities have contributed to this emergent phenological mismatch. In this study, we used remote sensing observations to systematically evaluate how plant phenological shifts have kept pace with warming trends at the continental scale. In particular, we developed a metric of spatial mismatch that connects empirical spatiotemporal data to ecological theory using the “velocity of change” approach. In northern mid-to high-latitude regions (between 30–70°N) over the last three decades (1981–2014), we found evidence of a widespread mismatch between land surface phenology and climate where isolines of phenology lag behind or move in the opposite direction to the isolines of climate. These mismatches were more pronounced in human-dominated landscapes, suggesting a relationship between human activities and the desynchronization of phenology dynamics with climate variations. Results were corroborated with independent ground observations that indicate the mismatch of spring phenology increases with human population density for several plant species. This study reveals the possibility that not even some of the foremost responses in vegetation activity match the pace of recent warming. This systematic analysis of climate-phenology mismatch has important implications for the sustainable management of vegetation in human-dominated landscapes under climate change.